Wartime letter discovered under Sompting Abbotts' floorboards links son to family’s past

/Pupils at Sompting Abbotts in 2018 with the letter from 1939 discovered beneath the school floorboards. Also pictured: Mrs Patricia Sinclair, Principal, (left) and Mr Stuart Douch, Headmaster (right)

The unearthing of a letter from 1939 at Sompting Abbotts' Preparatory School has connected an Australian man to his British family during WW2.

The letter found under Sompting Abbotts' floorboards

“It was a big surprise to learn of the letter’s existence,” said Craig Macbride, 53, of Melbourne, Australia.

The four-page letter is a palpable connection to his family’s history he knew little about. Hand-written in fountain pen, it lay undetected beneath an old dormitory at Sompting Abbotts, near Worthing, for almost 80 years until a workman spotted it.

The well-thumbed yellowing note is addressed to a boy called ‘Jim’, who was a boarder at the school during World War II.

Tracing 'Jim' across the world

Now, the school, intrigued by the letter’s discovery, has succeeded in tracking down the identity of Jim right across continents to Australia. Staff recruited the help of researchers from both the UK and Tasmania.

No surname for ‘Jim’ was included on the letter but Sussex historian Margaret Sear of Lancing History Group was able to use the street address to determine that Jim was Donald James Macbride, born in Richmond, London, in 1926, son to Colin and Ivy Macbride. She also ascertained that the entire family, including Jim's older brother David (born 1924 and also a Sompting Abbotts' pupil) had later emigrated to Australia in 1948.

There the trail ran cold. So the school contacted historian Betty Pilgrim of Tasmanian Family History Research. She discovered that sadly, Jim had died in 2003, aged 76, in Hobart, Tasmania, and that his wife Pat had passed away the following year. But she had some good news. Jim had a living relative: his son Craig, based in Melbourne.

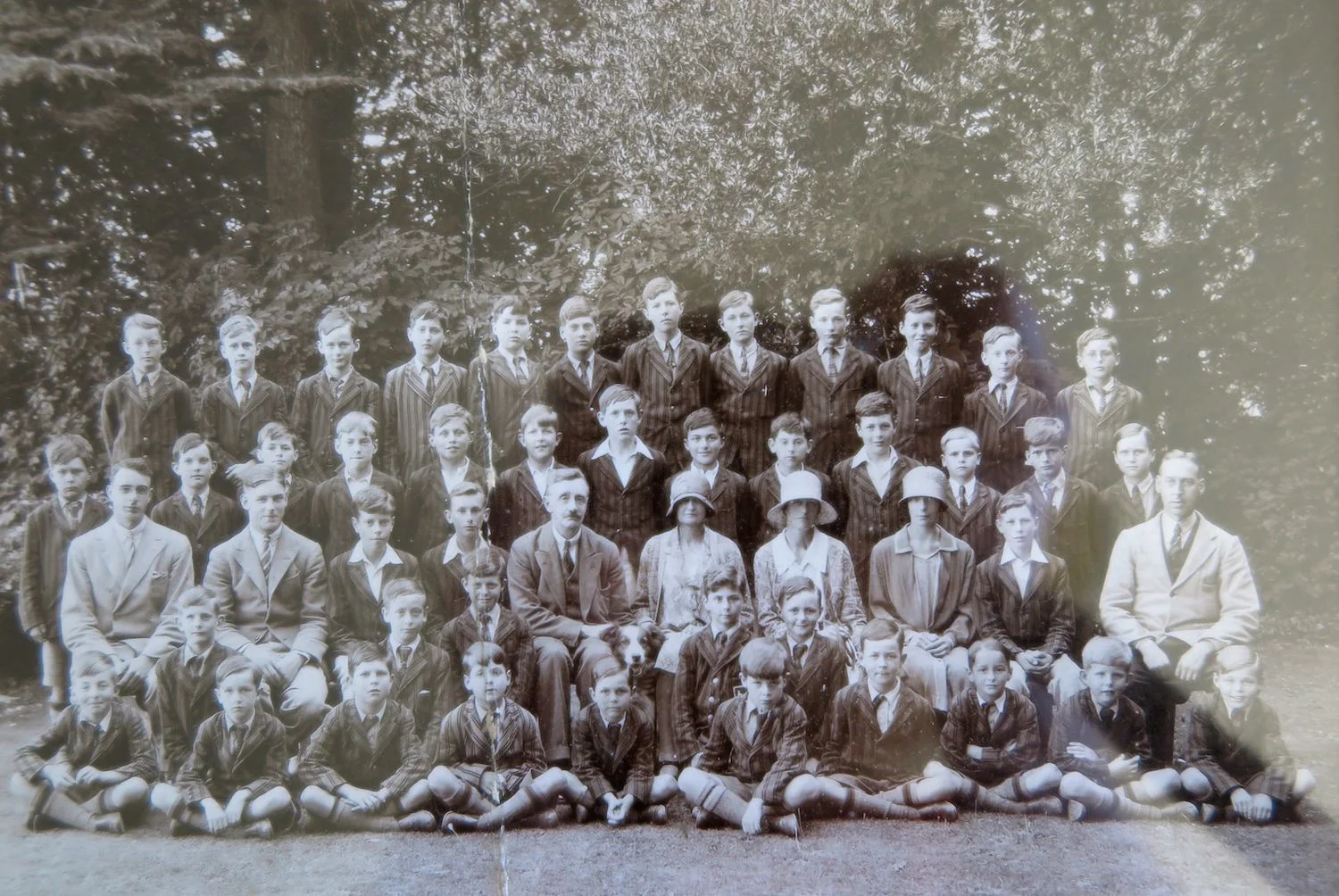

This archive image from the 1930s shows Sompting Abbotts' staff and boarders at the time: it's likely that Jim and his brother David are among the pupils pictured.

“It was an impressive bit of dogged detective work by the school to find me,” said son Craig Macbride, an IT specialist, born in Australia in 1964. The colourful letter from his grandmother to his father had given him a fascinating glimpse into his family’s past life in the UK.

Red letter day

Affectionately and poignantly written by Jim’s mother, the letter is a vivid description of her first experiences of the aggressions of war.

Jim's parents were then living on the naval base of Harwich where his father was probably naval personnel. In her letter, Jim’s mother tells him how she rushed to help British crewmen “covered in black oil and shivering cold” rescued from the sea after the destroyer HMS Gipsy was hit by a mine on 21 November 1939. She recounts how she dressed one freezing young sailor using “a pair of your shoes and a Sompting Abbotts' flannel shirt and your old flannel coat. It was a tight fit but better than nothing”.

The letter ends on a warm note: “Well darling, I look forward so much to hearing how the play progresses. I bet you all enjoy doing it. Heaps of love from Daddy. From your loving Mother PS Hope you got the skates safely. I sent them from the flat.”

How the letter came to be beneath the floor planks is unclear. Perhaps young Jim stored it under his bed and it slipped through a crack. Perhaps it was forgotten when he and his fellow pupils were hurriedly evacuated from the school in 1940 following the Surrender of France when the school building was requisitioned by the British Army.

1930s picture of Jim and his older brother David on a trip to London Zoo. They are both wearing their Sompting Abbotts' school uniforms of the day so perhaps this was a school trip. Image kind courtesy of Craig Macbride

The £10 Pommies

Image courtesy of NAA

Craig was aware, he said, that Britain was a pretty miserable place after the end of WW2. Rationing would still have been underway. "I knew my grandparents left for Australia to give my dad a better life,” he said. “But I didn’t know much about what their wartime experiences in Britain were like.”

The Macbrides were among thousands of ‘Pommies’ who chose to escape British austerity after WW2. Many took advantage of the £10 Assisted Passage Scheme funded by the British and Australian governments.

They opted to become ‘New Australians’ at a time when Australia needed to expand its population and was encouraging mass immigration. Its Assisted Passage Scheme was created in 1945 by the Chifley Government and its first Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, as part of the 'Populate or Perish' policy.

A ship arriving in Melbourne with immigrants from the UK in 1947. Image courtesy of NAA

It was intended to increase the population of Australia and to supply workers for the country's booming industries. In return for subsidising the cost of travelling to Australia — adult migrants were charged only £10 for the fare (hence the name; in 1945 pounds, equivalent to £396 in 2016), and children were allowed to travel free of charge — the Government promised employment prospects, housing, and a sunnier and happier lifestyle.

Craig said that his dad, Jim, had continued his senior school education at Framlingham College, Suffolk, after Sompting Abbotts Prep School. He had remained at Framlingham College until 1943 when he signed up to serve his country aged 18, serving as a Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in the Middle East. The war over, he followed the path of his engineering interest and qualified as a marine engineer at Northampton Engineering College.

Then, in 1948, aged 22, Jim emigrated to Australia with his family where he was drawn back to his military career, this time to the Royal Australian Engineers. From 1950 to the early 1980s, he served his adopted country and finally retired as a Colonel and Chief Engineer. In 1977, he received the Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal, awarded to individuals deemed to have made a significant contribution to their fellow citizens or community.

Craig said that Jim had been formed by his traditional British schooling. “He was disciplined and hardworking and encouraged me to do my best in life," he said. "‘If a job’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well,’ he would say. He didn’t speak much about his life as a child during the war in England. I think he wanted to forget it, much as I was interested in it. He did sometimes talk about air raid shelters and the panic of getting to them.”

Lessons in life

So what will happen to the original letter now? Craig has agreed that Sompting Abbotts Preparatory School should put it on display so that its story can be shared with the pupils of today.

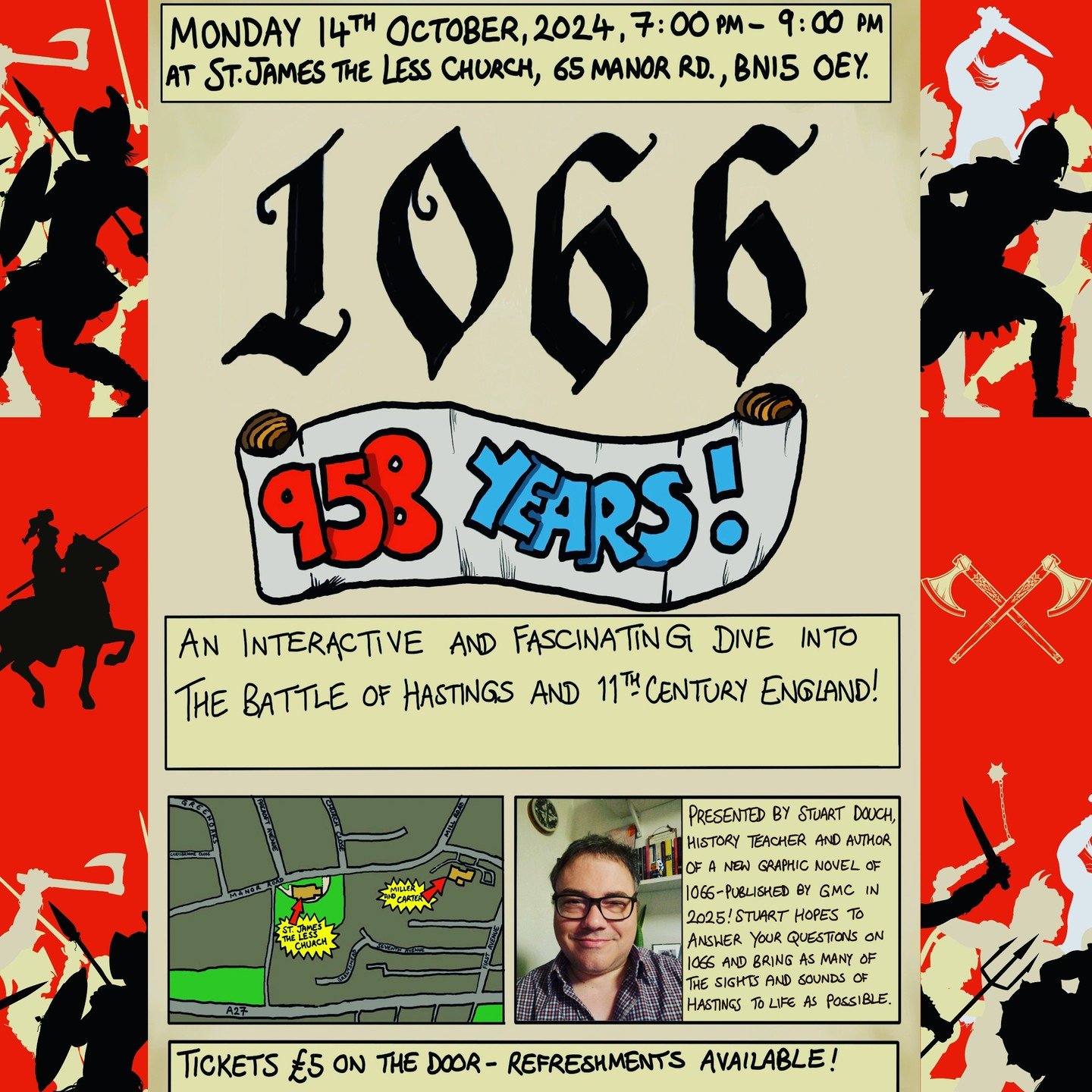

Sompting Abbotts Headmaster Stuart Douch said: “We’re so happy that the story of the mysterious letter has an ending. It has really captured the children’s imagination and stimulated their interest in this important period of British history.”

He added: "This letter to a former boarder is a fascinating insight for today’s pupils into WW2, made all the more relevant to them as Jim attended Sompting Abbotts too.”

Sompting Abbotts Preparatory School, housed in a Neo-Gothic building dating from 1856, was founded three years after the 1914-1918 Great War. It was a thriving boys' boarding school from 1921 until 1939 and the outbreak of WW2 when the surrender of France in 1940 forced the school’s temporary closure until 1946. The pupils were evacuated to Wales and the British Army requisitioned the house and grounds. The school became co-educational in 1998. It ceased to take boarders in 2008. Today Sompting Abbotts is a West Sussex independent day school for girls and boys aged 2 – 13.

Pupils at Sompting Abbotts Prep School display the letter written to a former pupil almost 80 years ago. It will now used in history lessons to help them expand on their understanding of the events of WW2

Below, you can read the original letter to Jim:

4, St. Helen's Green, Harwich, Essex.

November 22nd, 1939

Dearest Jim,

Many thanks for your nice interesting letter. I bet you all enjoyed the lecture on deep-sea diving.

I would love to be able to see the play, darling. I bet you will make a nice girl. I always said you ought to have been my daughter! Is it fun rehearsing?

I went to London on Monday and returned Tuesday about 6 o'clock. When I got back there was a message waiting for me from Mrs. Watson since 2 o'clock, asking me to go to the quay and help her take all the old clothes I could spare, as the Terakuni Maru (a ship Uncle Charles has travelled on) has been mined and sunk just off this shore and they were bringing in the survivors.

Of course I rushed off at once but was too late. They had all been given food and hot drinks and dry clothes and had gone up to London.

We sat down for an evening chat with the Watsons. At 9.15, there were two most terrible explosions. One of our own destroyers struck a mine only about 100 yards from the harbour. They brought in about 140 survivors and Daddy and I stayed all night and helped. We gave them hot tea and soup and biscuits. They were practically naked, just wrapped round in old blankets or any old thing and covered in black oil and shivering cold.

The destroyer HMS Gipsy hit by a mine on 21 November 1939, whose rescued sailors Jim's mother helped to clothe with Jim's outgrown Sompting Abbotts' school uniform. Photo: Imperial War Museum

We put them in dry clothes but we had only got women’s clothes for them except two young lads I helped into some clothes of yours and David's. One has got a pair of your shoes and a Sompting Abbotts' flannel shirt and your old flannel coat. It was a tight fit but better than nothing.

Some were badly injured and 25 have gone down with the ship. It was a terrible thing and my heart ached for those poor men. They were so brave; they joked and laughed at one another because they looked so funny in women`s clothes. The state they arrived in was pitiful and their poor bare feet were blue with cold. We only had a few pairs of shoes to give out so most had to remain bare footed. There were about four doctors working on those that were badly smashed up.

During this past week about 500 survivors from sunk vessels have been brought in to Harwich and given clothes, drinks, food, care and attention; not a bad effort. The clothes question is the most difficult. I have written to several friends and asked them to send us all the old clothes that they can spare so that we have a good store of warm dry things in case of emergency.

Well darling, I look forward so much to hearing how the play progresses. I bet you all enjoy doing it.

Heaps of love from Daddy. From your loving Mother

PS Hope you got the skates safely. I sent them from the flat.

BBC Radio Sussex interview Headmaster Stuart Douch about the wartime letter discovery